While he is inside, he is safe from the winter storms; but after a few moments of comfort, he vanishes from sight into the wintry world from which he came.

Bede, Ecclesiastical History (circa 627)

On May 7, 2001, in his reflections on the fourteenth birthday of the discussion group Humanist, Willard McCarty evoked the words of one of King Edwin’s counsellors, as recounted by Bede in Ecclesiastical History, to convey the transitional nature of the field of Humanities Computing:

We’re 14 years old now, a venerable age in this medium, like everything else somewhere between coming into being and going out of it, “like the swift flight of a single sparrow through the banqueting-hall where you are sitting at dinner on a winter’s day with your thegns and counselors. In the midst there is a comforting fire to warm the hall; outside, the storms of winter rain or snow are raging. This sparrow flies swiftly in through one door of the hall and out through another. While he is inside, he is safe from the winter storms; but after a few moments of comfort, he vanishes from sight into the wintry world from which he came.”

Humanist has been one of the few lasting, warm, indoor spaces where people in the humanities can discuss the digital. The metaphor of the swallow flying though the banqueting-hall captures what we would like our commons to be: warm, welcoming, and comfortable. However, we need to ask ourselves if our community is really a banqueting-hall of methods, ideas, and conversation.

The perceived importance of Digital Humanities has changed our sense of our community and inclusiveness. In this interlude we will take a retrospective look at the emersion of the term “Digital Humanities” through an analysis of Humanist. Using Voyant, we will look at the history of the field, discuss the data analyzed and the tools used, and discuss how the shift from Humanities Computing to Digital Humanities might be attributed to influence of the World Wide Web on the field.

Why Look Back Now?

In only a few years, Digital Humanities seems to have gone from a marginal field trying to gain respect to the favorite of university administrators. Digital humanists now need to define and justify what DH is to people who ask, rather than attempting to convince anyone willing to listen. It is difficult to pin down exactly when this transition happened.

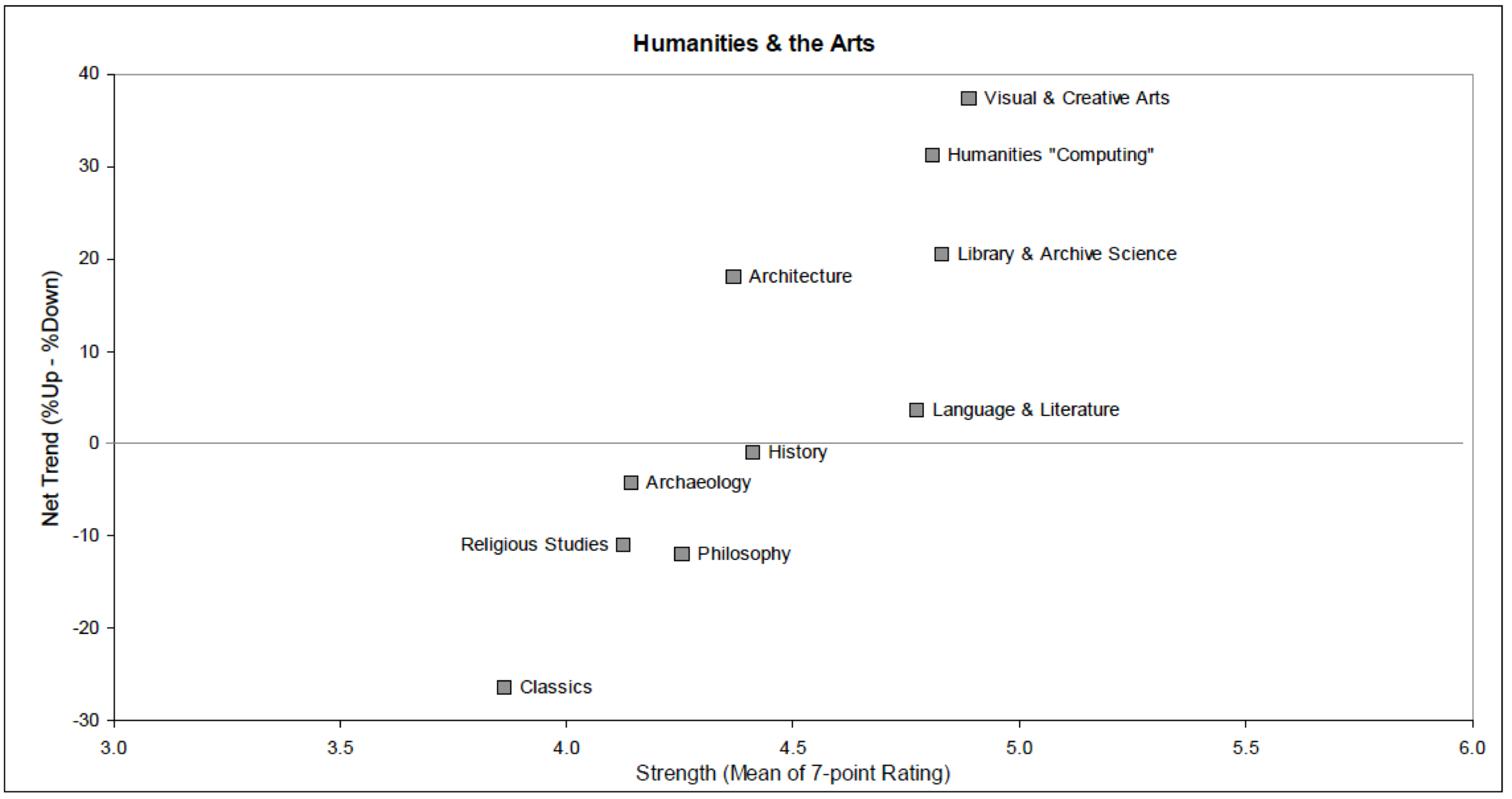

One important moment in the evolution of DH in Canada happened in 2006, when a report titled The State of Science and Technology in Canada, prepared by the Council of Canadian Academies, identified Humanities Computing as a growing area of Canadian strength. The report positioned Humanities Computing on a graph and in the text as an emerging transdisciplinary field “for which future prospects are seen to be more significant than currently established strength.”

Figure 1: A graph of trends of humanities and arts disciplines

There are a few other definitive moments in the establishment of DH as a field. William Pannapacker wrote, in a post to the Chronicle of Higher Education’s Brainstorm blog, that “amid all the doom and gloom of the 2009 MLA Convention, one field seems to be alive and well: the Digital Humanities.” He continued with the claim that “the Digital Humanities seem like the first ‘next big thing’ in a long time.” John Unsworth later noted in his 2010 “State of the Digital Humanities” address at the Digital Humanities Summer Institute that when a field is perceived to have jobs, while other humanities fields are seeing a dramatic decline, “it’s bound to attract some notice, especially among bright, goal-oriented graduate students who are approaching the job market.” As universities try to get into the game by posting not single jobs but clusters of jobs, and graduate students try to adapt to those jobs, issues of definition and self-definition become important. Stanley Fish, in posts to the New York Times’ Opinionator blog (2011, 2012, 2012), has declared the DH to be the latest swallow to fly through the MLA. Fish expects the digital, like any other theoretical fad, to become the establishment and then get exiled outside to the cold of yesterday’s theory. He may have missed the constructive side of the Digital Humanities—the digitizing of cultural evidence, the encoding of texts, and the development of tools—but he may be nonetheless right about how DH will eventually cease to be a new thing.

Funding agencies noticing and creating programs likewise played a significant role establishing the perceived worth of DH projects. Canada’s Social Science and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) introduced a funding program called Image, Text, Sound and Technology in 2003. In the United States, the National Endowment for the Humanities created Digital Humanities Start-Up Grants in 2007. In 2009, the Digging into Data Challenge brought together four national agencies, representing Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States, and funded eight international projects. We should not underestimate the degree to which money can draw academics into a space of practices.

DH’s self-conscious turn isn’t evident only in reports about the field from outside. It can also be seen in papers looking at the field, and asking questions about it, from the threshold. One example is David McClure’s “Visualizing 27 years, 12 million words of the Humanist list” and the accompanying visualization (humanist.dclure.org). Other examples include a 2009 paper by Xiaoguang Wang and Mitsuyuki Inaba that was presented in Taipei and then published in Art Research under the title “Analyzing Structures and Evolution of Digital Humanities Based on Correspondence Analysis and Co-word Analysis.” In that paper, Wang and Inaba performed correspondence analysis and co-word analysis on journals and conference proceedings. Patrik Svensson’s paper “The Landscape of Digital Humanities” (2010) (part of a four-part series on the field) similarly provides a “flythrough” of the DH landscape. Wang and Inaba used text-analysis techniques to ask about the shift from “Humanities Computing” to “Digital Humanities”; Svensson takes a cultural-studies approach, looking at the actors and the discourse. We are going to use the Humanist discussion list as a surrogate to study the flight of the swallow.

Data and Methods

The Humanist discussion list was started in 1987 by Willard McCarty when he was at the Centre for Computing in the Humanities at the University of Toronto. The first message introducing the list began this way: “Humanist is a Bitnet/NetNorth electronic mail network for people who support computing in the humanities.” The list is still running, and, after an interlude of a few years, is still moderated by McCarty. Humanist has limitations, yet it provides a rich text for understanding Digital Humanities in the English-speaking world.

Bringing correspondence analysis and other methods to bear, we analyzed 21 years of Humanist, from 1987 to 2008, stopping at 2008 because of problems with the archives after that year that interrupt the sequence (and because we already had the corpus prepared). We processed the archive files, and in the list below we name them in chronological order; you can recapitulate what have done using these Voyant collections.

- Humanist website and Archives

- Humanist in Voyant with normal skin and stopword list

- Humanist in Voyant with correspondence analysis (scatter-plot) skin and stopword list

Two goals of our methodological practice are to develop hypotheses in conversation and then to develop the tools needed to support their exploration. We adapted Voyant to handle the sort of corpus that allows us to do diachronic analysis and distant reading across the last decades of Humanities Computing. To facilitate the formation and exploration of hypotheses, we added a tool for analyzing correspondence, a skin (that is, an environment for interpretation) that connected a scatter-plot visualization of the results of correspondence analyses, and some other panels (for more on correspondence analysis, see Greenacre 1984; McKinnon 1989). Hypotheses were then tested using Voyant and other tools. We will use those hypotheses and the unexpected themes that emerged to discuss our flight through the corpus.

From Humanities Computing to Digital Humanities

We began with the expectation that the shift from “Humanities Computing” to “Digital Humanities” happened in middle of the first decade of the millennium. Though we certainly found that “Digital Humanities” was gaining momentum in 2004 and 2005, we were surprised that “Humanities Computing” continued to be a popular phrase.

Figure 2: From Humanities Computing to the Digital Humanities.

It is hard to pinpoint when and why the term Digital Humanities began to be used. The University of Virginia asserted early on that the term was more inclusive. In 2001–2002 that university hosted a National Endowment for the Humanities seminar designed to develop an MA program in DH. In his exploration of the term, Matthew Kirschenbaum (2010) reveals that in the early 2000s an acquiring editor at Blackwell, while preparing the Companion to Digital Humanities, played an important role in coining the term. That book’s contents and its title have been enormously influential. The founding of the Association of Digital Humanities Organizations (ADHO) in 2005 certainly added administrative weight; other names, among them International Consortium of Humanities Informatics Organizations, were considered and rejected. In Canada, the renaming of the Consortium for Computing in the Humanities to the Society for Digital Humanities / Société canadienne pour les humanités numériques in 2005 influenced the usage of the term Digital Humanities in Canadian scholarly circles. The creation of the National Endowment for the Humanities’ Digital Humanities Initiative in 2006 was decisive role, and the creation of the Office of Digital Humanities in 2008 solidified the NEH’s interest in funding digital scholarship in the humanities.

Although the public archives from Humanist are suitable for epidemiological studies (to tell you what happened and what correlated with that happening), it doesn’t show causation or motivation. A computer, like Searle in the Chinese room, doesn’t know anything about the symbols it processes. One must interpret their meaning and examine the question from multiple angles.

The Passing of Centers

Figure 3: Distribution graph of “center” and “centre” in Humanist Discussion Group listserv archives.

Second, we hypothesized that the cause for the shift to DH might be found in the move from center-based computing research to personal-computer-based processing. Universities’ humanities computing centers made networked computing available in labs in the 1980s and the 1990s. Once high-speed Internet connections to homes were available, DH shifted to a distributed project model. Alas, we did not find evidence to corroborate our hypothesis. Although the word “project” becomes more popular, and although some centers have closed, other centers have started up. Our experience with the closing of certain Canadian centers, including the Centre for Computing in the Humanities at the University of Toronto, biased us into thinking that it represented a larger phenomenon. It is, however, interesting to plot the coming, going, and transformation of centers over time.

The Turn of the Web

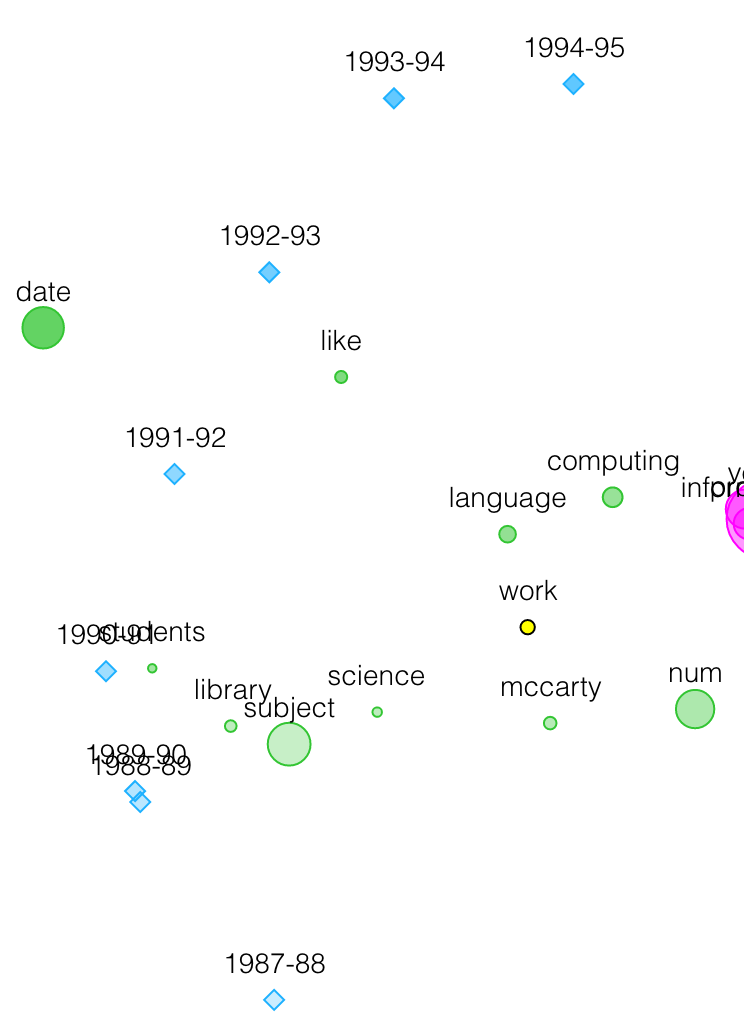

The most dramatic evidence of change was so obvious that we didn’t think or hypothesize about it until we had developed a tool that could use correspondence analysis to show clusters of years and key words.

The scatter plot in figure 4 displays the major word clusters generated by correspondence analysis. It shows a strong pull of “Web,” “www,” and “html.” There seem to be three phases in the data studied, at least based on the groupings found in the correspondence analysis: from 1987 to 1995, when Humanities Computing was taking place in English departments and/or in the English language and was interested in computers, software, hardware, and texts; from 1996 through 2000, when words related to the Web increased; and from 2001 to the present.

Figure 4: Scatter plot of major dimensions from correspondence analysis of Humanist Discussion Group listserv archives.

Figure 5: Zoomed view of correspondence analysis of Humanist Discussion Group listserv archives

We now believe that the introduction of “Digital Humanities” represents not only an administrative change but also a change in the way electronic texts were consumed. The increasing use of the Web by humanists in the mid 1990s transformed the field, as the Web provided a way of distributing and publishing electronic editions of texts. This may explain why less and less of our discussion was about hardware and software and more and more was about services.

Figure 6: Distribution graph of “hardware,” “services,” and “software” in Humanist Discussion Group listserv archives.

In the 1970s and the 1980s, as personal computers became available, Humanities Computing was concerned with supporting the new hardware and software. The computer came in from the machine room to our warm studies. Humanist was initially conceived as a discussion list for those who supported others trying to use the new hardware and software. In 1986 many humanists were beginning to use computers for word processing; most did not have email, let alone stable Internet connections. Later, with the Web as a canvas for digital projects, we began to pay less attention to “processing” and more to “methods.” We began to reflect on content after the hard work of making scholarly electronic texts. Above all, we returned to “content,” going beyond text to look at other “media” and the “social.”

Figure 8: Distribution graph of “social,” “media,” and “content” in Humanist Discussion Group listserv archives.

It should also be noted that the Web made the digital more accessible. Although we would position ourselves on the hacking side of the “hack and yack” discussion, the trend mentioned above suggests that DH now concerns itself less with the making of tools and more with theory and criticism of digital content and digital methods. Perhaps the field is finding a balance or that our conception of what it means to make is changing.

Figure 9: Distribution graph of “make” and “critical” in Humanist Discussion Group listserv archives.

DH is not defined or determined by a single technology. Its concerns, however, were influenced by the Web and by the opening of a space of opportunity for self-publishing, both of which changed the field. To what extent are digital humanists responding to the possibilities of new technology? Is DH technologically determined?

Conclusion

The newfound prominence of the Digital Humanities in academia provides an opportunity to reflect on how the discipline has evolved and what it has become. One way to reflect is by re-reading Humanist using the tools and methods of the Digital Humanities. Such a re-reading can help us understand who we are and what might have influenced us. Of course, this is just our fly-through of a corpus; with accessible Web archives, and with Voyant, the hall is open to other birds of a feather.

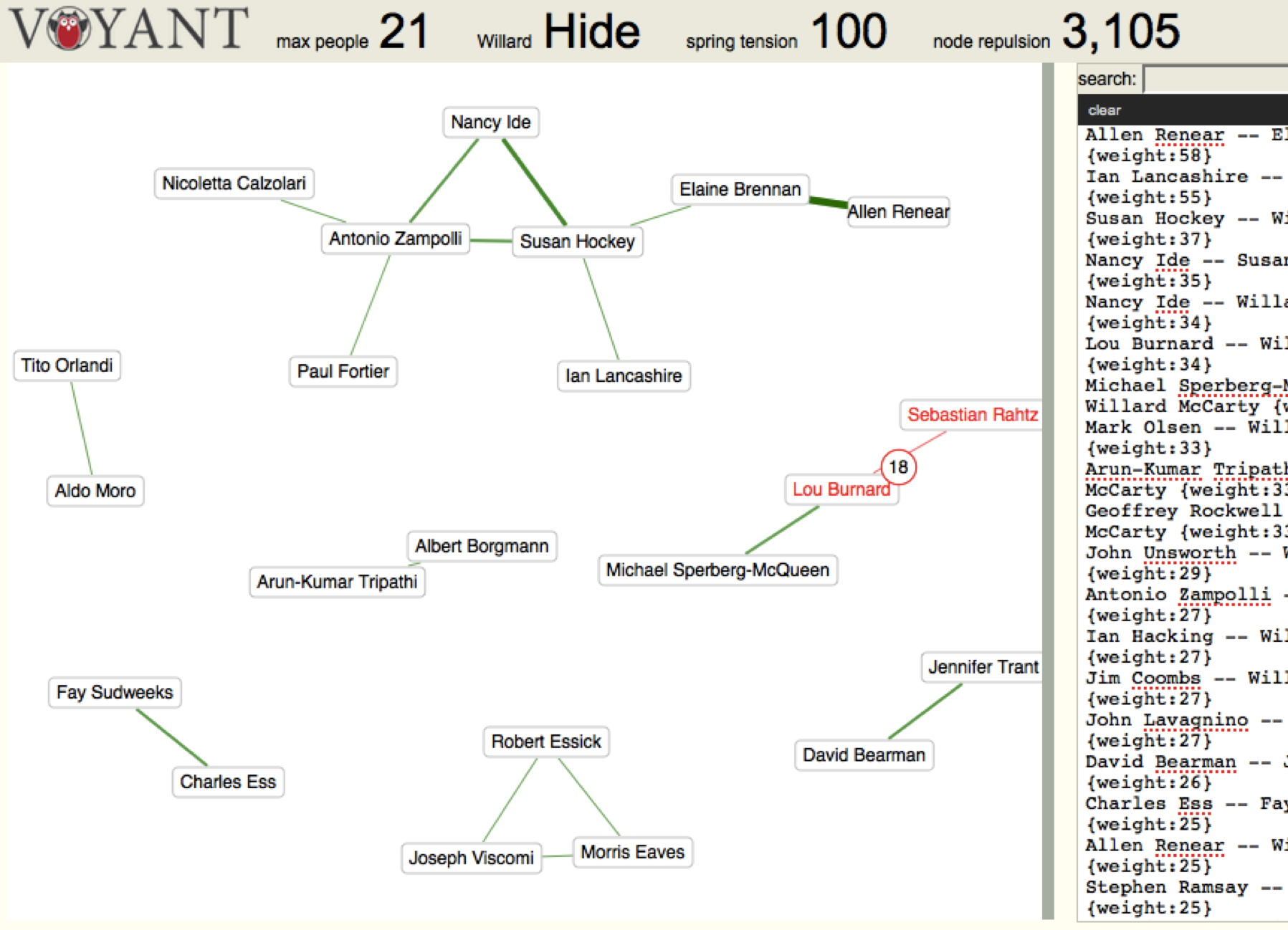

We leave you with another way of re-reading the archives—one that focuses not on the tools, but on their makers and their users. Figure 10 shows a tool that generates diagrams of social networks from archives (see also Name Games). It uses the Stanford Named Entity Recognizer (NER) to identify people, and then counts people who co-occur in Humanist messages (a word of caution: automatic tagging of people is messy and noisy). We treat these co-occurrences as a connection and count the number to weight the connections, though the types of connection may differ—for example, Tito Orlandi is connected to Aldo Moro (the Italian politician) very differently than Antonio Zampolli is connected to Susan Hockey.

Figure 10: RezoViz view of Humanist Discussion Group listserv archives.

Rockwell, Geoffrey and Stéfan Sinclair. “The Swallow Flies Swiftly Through: An Analysis of Humanist” from Hermeneutica: The Rhetoric of Text Analysis, MIT Press, 2016.