Sounds like he talked a hate speech, doesn’t it? Now, analyze that!

—Jeremiah Wright, 2008

In the lead-up to the 2008 US Presidential election the news media became interested in what Barack Obama and his spiritual mentor Jeremiah A. Wright Jr. had to say about race. Obama and Wright were represented as engaging in the age-old conflict between the son and his father, as the son comes of age as a leader. In the media’s imagined oedipal-drama, Obama, the son, tries to distance himself to win the presidency. Wright, the father-pastor, continually corrects the record while managing mounting media attention. In attempting to redirect attention to more substantive issues by asserting, “this time we want to talk about [X],” both men give moving and important speeches on race in the context of the USA. Wright even challenges us directly: “now analyze that!”

What if we took them at their word and looked away from the podium-and-pews drama? What if we take them seriously and look at what they say? What if we used our hermeneutica to try to “analyze that,” interrogating and interpreting the similarities and differences between their speeches? We took up their challenge. Using the tools we had at hand, including the first version of TAPoR and an earlier version of Voyant, we compared and analyzed two speeches given by the two men.

We chose to look at:

- Barack Obama’s March 18, 2008 speech “A more perfect union” given in response to the media attention. This speech has been generally considered one of Obama’s finest on race and America.

- Jeremiah Wright’s April 27th speech to the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP) that follows Obama’s speech; it also deals with race.

Here are both speeches loaded into Voyant:

We chose these speeches because we were not interested in the “gotchas” that bloggers and media focused on, like Wright’s references to Louis Farrakhan1, and we were able to find reasonable transcripts for both with associated video records. Moreover, these were important speeches, documents to which people were returning to understand Obama and Wright’s positions. Why not analyze that?

As we saw in the last few chapters, much of computer-assisted text analysis is essentially about tokenizing, counting and comparing, and quantities are not everything. Hermeneutical tools can show you the differences in word use; the results plant a seed to think about. This chapter will look at why the difference in what Obama and Wright’s say is worth thinking-through.

This Time We Want To Talk

One of the first things we noticed was that Obama uses the word “time” far more often than Wright. At the climax of Obama’s speech, he repeatedly uses the phrase “this time we want to talk.” This table shows a concordance of all the instances of “time.”

Repeated phrases are usually an indication of something the author wants to emphasize. In this case they are at the climax of Obama’s speech and tell us three things.

- This is the time. Obama wants us to be aware of the moment – a moment when an African-American could become president. Different times call for different discourses and “this time we want to talk about …”

- Not this time. Obama is trying to redirect what we, including the electorate and the media, are talking about during the election. He wants to elevate the discourse, to focus on what he believes should matter to the electorate, and to focus away from the identity politics that tars him along with Wright. For Obama, Wright acts as a distraction. Obama’s platform is firmly grounded in the promise of change. However, if the media continues to be diverted by the undo attention they are giving to Wright, the status quo will remain. “I can tell you,” he worries, that unless something changes, “that in the next election, we’ll be talking about some other distraction. And then another one. And then another one. And nothing will change.”

- We want to talk about. Obama emphasizes the importance of specific topics by claiming “we want to talk about [them].” In terms of location and rhetorical power, the repetition of the phrase marks the climax of this speech. Obama marks important topics, topics we should pay attention to, with the full phrase: “this time we want to talk about.”

There are five things Obama wants us to talk about. They are a fairly traditional list of democratic talking points, including education, health care, job at home, outsourcing, and the war in Iraq.

- Crumbling Schools – Education

- Lines in the Emergency Room – Health Care

- Shuttered Mills – Loss of Manufacturing Jobs

- Shipping Your Job Overseas – Business Outsourcing

- Serving and Fighting Together – The War in Iraq

However, Obama frames standard topics slightly differently; he invokes race to suggest that these issues transcend it. He claims, “this time we want to talk about the crumbling schools that are stealing the future of black children and white children and Asian children and Hispanic children and Native American children.” This time, he argues, focus should not be on the distractions that otherwise hijack elections. The election should direct focus to the issues that all Americans—black, white, Asian, Hispanic and indigenous—have in common.

Committed to Repetition

Wright similarly repeated one phrase, “we are committed to changing the way,” to focus attention on topics he saw as critical commitments. The distribution graph for “committed” likewise locates Wright’s phrase near the end his speech, at the rhetorical climax. A concordance of the word “committed” in Wright shows a pattern use:

Wright asserts that, together with his audience, he is committed changing the way the world is treated. The heart of his message appears in his use of the terms: “different” and “deficient.” Wright wants people to recognize that difference is not deficiency. He notes that,

In the past, we were taught to see others who are different as somehow being deficient. Christians saw Jews as being deficient. Catholics saw Protestants as being deficient. Presbyterians saw Pentecostals as being deficient.

Folks who like to holler in worship saw folk who like to be quiet as deficient. And vice versa.

Whites saw black as being deficient. …

Europeans saw Africans as deficient.

Difference, for Wright, should not be negated; it should be accepted. Wright invokes the differences between African and European music to outline his point:

Now, what is true in the field of education, linguistics, ethnomusicology, marching bands, psychology and culture is also true in the field of homiletics, hermeneutics, biblical studies, black sacred music and black worship. We just do it different and some of our haters can’t get their heads around that.

Our hermeneutica revealed a political difference in the minor discursive patterns: Obama sees challenges common to all. Wright sees differences that need to be recognized in order to be treated. As a presidential candidate, Obama wants us to turn our focus to the challenges we have in common, on what is wanting in the country as a whole. As a minister, Wright asks us, to make a commitment to see difference not deficiency.

Obama is trying to turn electoral discourse to political issues that administrations can solve. Wright is trying to refocus media criticism onto change, change individuals can commit to.

Black and White

Despite their frequent use of the inclusive word “we,” the speakers also focus on “black” and “white.” A Word Frequency List of the combined texts illustrates that, at a fundamental level, the speeches are about race, but then we choose them for that purpose.

“Black” is the highest frequency word. The speeches are obviously tailored to location and audience. Speaking on the perspective of the black church to the NAACP, Wright uses the word “white” only 4 times. Obama, speaking at the National Constitution Center, used the word “white” 27; on one occasion mentioning his “white” grandmother.

Text analysis on these two speeches illustrates how Obama distances himself from Wright’s use of “incendiary language to express views that have the potential not only to widen the racial divide, but views that denigrate both the greatness and the goodness of our nation; that rightly offend white and black alike.” Although he has some sympathy for his “religious leader’s effort to speak out against perceived injustice,” Obama unequivocally condemns Wright as being divisive.

As such, Reverend Wright’s comments were not only wrong but divisive, divisive at a time when we need unity; racially charged at a time when we need to come together to solve a set of monumental problems—two wars, a terrorist threat, a falling economy, a chronic health care crisis and potentially devastating climate change; problems that are neither black or white or Latino or Asian, but rather problems that confront us all.

Conversely, Wright is insisting that there are real differences, and by implication there are divisions that must be acknowledged, even if the act of acknowledging them is a politically charged one.

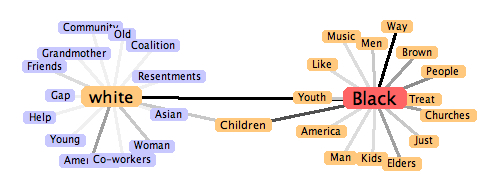

We close with a view of the collocates of the words “black” and “white” in both speeches. As we will later also see with Hume’s Dialogues, collocates are words that appear near the words in question. This static visual collocation should provoke you to think about how Obama and Wright talk about black and white. Look closely and you will discover that neither speaker uses the phrase “White House,” preferring to refer to the “Oval Office.” Why not take up Wright’s challenge and try to “analyze that” for yourself?

- 1. We looked at Wright’s speech to the National Press Club on April 28, 2008, but chose not to use that speech because a large portion of it took the form of question and answer (despite our interest in dialogue!) and therefore would not necessarily reflect how Wright wanted to shape the issues Wright, “Transcript: Rev. Jeremiah Wright speech to National Press Club.”