the two greatest and purest pleasures of human life, study and society

David Hume, Dialogues

In Hume’s Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion (1779), one of the great philosophical dialogues of the eighteenth century, a fictional author-narrator named Pamphilus describes a conversation among Philo (a sceptic), Cleanthes (a theist), and Demea (a fundamentalist) about God’s existence and God’s nature.

Hume wrote Dialogues late in life but did not publish it during his lifetime, fearing negative reactions to Philo’s sustained attacks on proofs of God’s existence. He hoped that friends (Adam Smith among them) would publish it after his death, but they demurred. Hume’s nephew arranged for it to be published two and half years after his death (for a good description in Italian of the history of the text, see the second chapter of Carabelli’s Hume e la retorica dell’ideologia (1972).

We began our inquiry into Hume’s work by asking what we could learn about scepticism from the it using text analysis. Scepticism interested us because it is an approach that underlies much of what we think about knowing, and because much of this book is about how computational tools can help us in thinking through.

Sceptical attacks on knowing have provoked many of the most imaginative attempts to methodically ground human knowledge. Descartes interrogates knowing by sceptically doubting everything, including what others have to say; this leads to “I think, therefore I am.” Scepticism is a tradition of systematically questioning any certainty, including our certainties about the existence of God and, as in the case of Descartes, our belief in any reality.1 Sceptics even doubt their own rationality and doubt scepticism itself. Scepticism, at least as it unfolds in the Dialogues, is a particularly recursive and postmodern artifice of inquiry.

The problem with scepticism, as is pointed out in the Dialogues, is that when the conversation is over you end up not being able to believe in any knowledge, even whether doors or windows are the best exits from a building. For some sceptics this is a relief. One extreme school, which runs from Sextus Empiricus and other Pyrrhonian sceptics to the later Wittgenstein, believes that philosophizing is a disease and that sceptical questioning of all beliefs leads not to deeper knowledge but to giving up philosophizing. Scepticism, for these anti-philosophers, leads to a state of suspension of belief that then helps one regain a sense of balance and achieve release from the anxieties of philosophy. In giving up figuring out what you know, you are released back to a more humble and balanced life in which you use doors as exits instead of questioning their reality. If you think you think too much, scepticism is the cure for you, as it is a cure by thinking through thinking.

More important, the tradition of sceptical questioning, as found in Hume’s Dialogues and in many other philosophical works, creates space for agile interpretation instead of trying to permanently solve interpretive questions. Just as Plato, Cicero, Diderot, and Hume use the philosophical dialogue form to illustrate ways of being intellectually in a world where differing opinions are tolerated, so computer-assisted methods of interpretation can open spaces of interpretation rather than trying to resolve things definitively. We are all sceptics to some degree, open to the idea that our most cherished theories could be proved wrong and always interpreting evidence and tradition. We are eager to encounter new evidence as the total space of understanding is enriched by the diversity of possibilities and interpretations, and, as Steven Ramsay has pointed out, the computer is an excellent tool for generating new evidence to consider. What better text to interpret with the help of hermeneutica than an artificial dialogue that models the questioning of certainties, methods, and results?

This chapter, our final interlude, is designed to show how you can do sustained text analysis across a single prepared text. Where does one begin when studying a text? The cost of entry can seem dauntingly high for a textual scholar contemplating all the tools, technical terms, and methods that one must master just to decide whether a computer can help. Playing with a text you know well is one way to start. For this reason, in this chapter we will give you a sense of what doing complex text analysis is like by telling the story of our interpretation of Hume’s Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion. This artifice of a story of interpretation is designed to illustrate how you can use Voyant to study a single text that you already know but are re-searching.2 On the way we will also talk about the dialogue of interpretation and about where text analysis can fit in a hermeneutical process.

Start by Bringing Questions to a Text or a Text to Questions

Our first step was to identify a text we knew well that we wanted to question. We then discussed questions we wanted to ask of Hume’s Dialogues. (Starting with a text you know is a good way to test whether computer-assisted text analysis can provide further insight, as familiarity provides starting points for inquiry.)

Try Voyant on a text you know, one you have found or written, and see if interactive visualizations can show you something new. Test how it plays with the reading practices you have already developed. Alternatively, start with questions for which you then have to develop a text or collection of texts. We provided examples of these sorts of projects in the chapter 6, where we started with questions about Barack Obama’s position on race and proceeded to find, analyze, and interpret his speeches on race.

You could begin with a single text or work or with a body of works—an artificial “corpus” or collection. Either way, as you find and prepare a text, you should develop initial questions or hypotheses that you want to explore using hermeneutical tools. Don’t worry too much about your starting questions; you will find the questions change as you delve deeper into the text. You will discover anomalies in results offered by Voyant that spur new lines of enquiry. New questions will come faster than answers.

Adapt Questions to Hermeneutica

To do text analysis you need to formulate and formalize your questions, at least initially, into something that the searching, matching, counting, and visualizing capabilities of a text-analysis tool can help you with. You can’t just ask what themes are important in a text, or what the text has to say about friendship; however, you can ask what clusters of words (which might indicate themes) have a high frequency (which might indicate importance), and you can ask to follow a cluster of friendship words through the text. This formalization is the hard work, but it is also where you practice thinking through analysis without even turning on the computer.

Even though you will have to formalize questions in order for the tool to be able to produce results, it is important to remember that the interpretive enterprise, as a whole, is not limited to computational results. You can use results produced by the tool to ask further questions or formulate arguments that are pursued by other means. Interpretive text analysis is a hybrid practice, one that is only assisted, or augmented, by the tool.

The Text You Use Matters

For our experiment we looked for an electronic edition of the Dialogues that we could mount in Voyant. We chose the Project Gutenberg version chiefly for pragmatic reasons: the text is freely and readily accessible.3 Scholars should always carefully double-check text editions, even those sourced from well-established projects such as Project Gutenberg. They should be sceptical of the quality, and should check passages against other editions, especially for terms that matter to the analysis. Sometimes a digitized text is not the best version; sometimes a digital version contains typos or even missing chapters; often there are extra metadata in the text. We periodically cross-referenced this digital version with a print edition.

Analysis Develops Many New Texts

A text-analysis research cycle generates many intermediate model texts. The cleaning and preparation phase—isolating the body of the text from the metadata, correcting flagrant typos, normalizing titles and other structural elements, creates a version. The second phase, breaking apart the text in various ways to create new texts, creates additional versions. Analysis, in the etymological sense of a breaking something into parts, by its very definition produces new fragmentary texts. These parts gets recombined in different ways into new hybrid texts or “results” that you can save and use for further reading and analysis. It is like a branching dialogue of potential texts.

In the course of our experiment, we found ourselves saving numerous intermediate results and having to make sure we noted how they were generated in case we wanted to recapitulate or explain how we produced them. The combinatorics of this get even more dizzying as branches are made and corrections or adjustments must be applied to multiple versions. It is critical to keep track of the many texts. We accomplished this through expressive but succinct file-naming strategies.

To support different types of questions, we created different input texts for different tools. We first converted the plain-text file into an XML representation in which important structural features were tagged—especially chapters, titles, speeches, and paragraphs. Producing XML representations may be excessive in a lot of instances where a text can be treated as a simple sequence of words, but it was necessary for our purposes in order to produce multiple views of the text. This allowed us to create separate documents from each of the chapters (also called books or parts) in Hume’s Dialogues (For the purpose of this study, we will use the term “chapters” to identify the segments of the Dialogues). Adding tagging for the speeches uttered by each character allowed us to recombine all the speeches from each individual character into separate documents. Not only is such tagging useful for creating new texts as views of the source text; it also makes it easy to apply styling when viewing each representation. For instance, we have a view of the full text in which the words of the different speakers are colored to make it easy to see who says what.7 We would like to say that we anticipated all these needs and created all these variants at the beginning, but the truth is that we had to go back and create new input texts as new questions arose. New texts are produced iteratively as needs arise; data are taken and remixed, not merely given.

Here are some useful links:

- a colour-coded (and marked-up) version of the Dialogues

- a Voyant corpus divided into parts (chapters)

- a Voyant corpus divided into speakers

Analysis Unfolds through the Iterative Development of Model Texts

Returning to the starting issue of scepticism, we then had to decide how Agile Hermeneutics could help us think through the scepticism in Hume’s dialogues. Hume’s dialogues, like other philosophical dialogues, are hard to interpret if what you want is to figure out is what the author thought, because nowhere does Hume write in the first person (though even if had it may not help determine authorial intent, as we know well from literary criticism). The narrator who tells the story of the dialogue (in a letter to Hermippus) is Pamphilus, not Hume, a hint that the narrator should not be confused with the author. Understanding scepticism in the dialogue will depend on understanding its dramatic structure and asking how different characters might represent (or not) different positions the author considers relevant. How then can we read Hume’s presentation of scepticism in this work that is not in his voice?

Analysis Is a Comparison with a Model: Looking at Characters

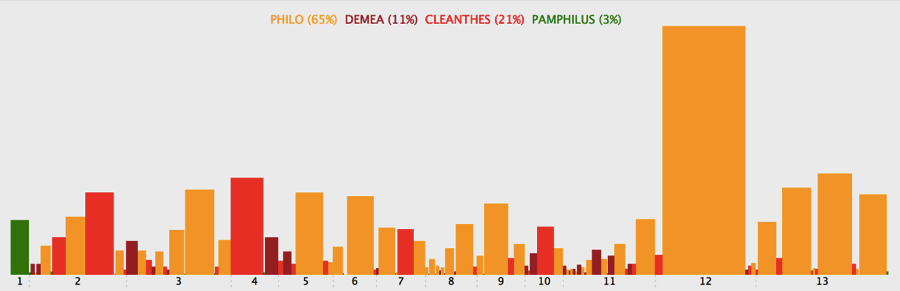

The easiest interpretation of a dialogue is to see if there is a principal character who may stand as a model for the author the way Socrates does so often in the Platonic dialogues. Assuming that quantity represents authority, we measured the number of words each character speaks to see if one character is speaking more often. Text tools give us a way to do this. We decomposed the full text into subtexts by character and compared those subtexts with other subtexts in different ways. You can use Voyant’s Summary, or any tool that counts words, to ask which character speaks the most.

Figure 1 Voyant Summary. To get this summary we created a corpus with the extracted texts for each speaker. This corpus then treats each speaker’s text as a document in a larger corpus and counts the words for the documents. Note that the text has the same words, but out of order.

According to the lexical counting algorithms of Voyant, Philo has 23,085 words, Cleanthe 7,455, and Demea 3,998. Philo talks three times as much as the next most verbose other speaker, Cleanthes; that is a dramatic difference. The scale of Philo’s speech acts would seem to confirm what most readers instinctively end up believing: that Philo is set up to be the hero of Hume’s Dialogues. One could cautiously assume Philo represents the position Hume wants us to take most seriously as you cannot help but sympathize with Philo through the dialogue.

Figure 2: Distribution of Speeches by Speaker. The parts are numbered starting with Pamphilus’ prologue, and thus the numbers are off by +1.

Experiment through Code and Visualization

Once we realized the magnitude of the difference in how much the speakers talk, we remembered that some chapters seem to be mostly Philo talking; those chapters can hardly be called dialogical. Other chapters, however, have more lively exchanges. To further examine the difference, we decided to graph the speeches against chapters to see where there are long speeches and where there is more exchange. For this visualization we wrote custom code, though one could do it manually entering word counts into a spreadsheet. We have found that we almost always want to go beyond what a tool such as Voyant can do when pursuing questions. That is an argument for learning different tools or some basic programming skills. After a number of iterations we ended up with figure 2, which clearly shows the large set-piece speeches near the end of the Dialogues, in chapters 11 and 12 (labeled sections 12 and 13 in the figure), in comparison with the tighter exchanges earlier in the Dialogues. It almost graphs the drama of the dialogue climaxing at the beginning of chapter 10, at least insofar as exchange indicates drama. Philo then dominates the last two chapters. He has one long speech in chapter 11; in the last chapter he has four medium length speeches broken by short exchanges. The Dialogues consist of an introductory letter by Pamphilus and twelve parts. In some editions the parts are called books. Here we stick with Tweyman’s labels, though in some of our visualizations you will see thirteen sections (the introduction plus 12 parts.) In other visualizations you will see ten divisions that represent 10 percent chunks of the text.

Synthesize New Views for Comparison

Graphs are one of the engaging outcomes of interpretive tools. They can be fascinating to explore and frustrating to translate into prose; it is no surprise that the overabundant digital visualizations on the Web are accompanied by little or no commentary. (See, for instance, the beautiful but under-interpreted visualizations of the Lord of the Rings at http://lotrproject.com/statistics/books/.) Good visualizations seem to articulate meaning, but that meaning is difficult to define, at least in words.4 This shouldn’t surprise us as visualizations transcode text into images—they create new visual texts or pictorial concordances by translating textual code into visual code.5 One might wonder if they really need to be further interpreted, or if that is a discursive habit. Just as art is meant to be individually and idiosyncratically experienced, we might want to allow for aesthetic visualizations that produce irreproducible effects, especially when they are interactive in ways that would be difficult to re-enact.

Our visualizations are artificially generated models of Hume’s original text; readers should be sceptical of what our visualizations show and what they hide. Like any interpretation, they produce meaning differently for different people. Therein lies the challenge of text analysis: it can be fascinating for those involved in the modeling but impenetrable to those who aren’t accustomed to computer-based methods or aren’t familiar with the nature of a particular model.

Model Visualizations for Serious Play

As facilitated by computers, interpretive tools and embeddable toys can do a number of useful and interesting things, such as the following:

- Do tedious searching, counting, manipulation, and data-plotting.

- Facilitate interaction. Some visualizations dynamically change according to a user’s actions.

- Present us with models that make the text strange so as to provoke further thinking through.

- Transcode the text into something we can play with in new ways; simulate the tactile pleasure of having in our hands a model aircraft or a Visible Man or Visible Woman that we can learn from by playing with it.

- Remind us that software doesn’t replace human labor but rather is a tool that can extend our reach or augment our intellect.6

The visualizations we produced with Voyant, although interesting, didn’t help to answer our question about Hume’s scepticism as it is presented in the Dialogues—especially at the end, where Philo recants. After spending the whole dialogue as a model sceptic who breaks apart arguments for the existence of God, Philo changes tack in the final chapter and acknowledges the obviousness of God’s existence: “Notwithstanding the freedom of my conversation, and my love of singular arguments, no one has a deeper sense of religion impressed on his mind, or pays more profound adoration to the Divine Being, as he discovers himself to reason, in the inexplicable contrivance and artifice of nature.”7 And Pamphilus—the fictional author-narrator telling us of the dialogue, and a candidate for Hume’s final judgment—concludes the dialogue by telling us that he prefers Cleanthes’ “accurate philosophic turn” to Philo’s “careless scepticism.”8 If the narrator for whom this conversation has been staged, and who reports it to his friend in a letter, closes the work with such a judgment, we need to consider whether it hints at how we should interpret the work. Perhaps Hume doesn’t think Philo’s position is the whole story. Perhaps Hume is playing with his reader.

Analytics Show There Is Something; Interpretation Judges Meaning

Philo’s sceptical reversal illustrates one of the dangers of text analysis and visualization: The tools can show you where characters speak and how much they speak, but they don’t tell you what the speaking means. Only a reader of the text would know that there is a surprising reversal in part 12 that seems to undo all of Philo’s persistent questioning. The graph reproduced here as figure 2 shows only that Philo gives several long set-piece speeches at the end, not how or why he changes his mind.

We may get human-quality interpretation from computers someday, but at the moment computers are not very good at finding or defining meaning. It is questionable if they will ever match our human ability to sniff out irony or other forms of layering meaning. True artificial intelligence has seemed just beyond our grasp since early successes of the 1960s. That is why returning to the text to confirm interpretation is critical.9 and why Voyant puts a reading panel in the center of its main reading skin, an environmental mode, to make it possible to get at the original text. We believe that text analysis is a form of re-reading or reading through; the original text should be revisited alongside new forms of data analysis and visualization.

Literary Analysis Returns to the Text

Philo’s reversal has puzzled interpreters of Hume for some time; many are tempted to dismiss it as a ploy by Hume to mask his radical scepticism.10 Is it just Hume trying to play it safe by tacking back to religion at the end of his dialogue in a way that makes doubly sure that he can respond to accusers that his most talkative character is not an atheist? For that matter, is Philo actually recanting, or is there a subtler interpretation of his evolving position? In short, the reversal raises questions not only about Hume’s position on the existence of God but also about Hume’s variant of scepticism as a philosophical practice.

If Philo seems to be constructed by Hume as an example of how a sceptic should argue, what does it mean when the sceptic flip-flops at the end and is judged second to the theist? Is that a sign that Hume actually found scepticism wanting? Does it signify that Hume advocates switching positions to suit the audience? Could Hume be showing a deeper scepticism of scepticism? We need to look more closely at how scepticism is discussed in the dialogue, and text analysis can help us to do so.

Following a Theme

Software cannot summarize a theme the way a human would. However, it can identify the words that would mark the theme and then track their interactions through the text. This is not new functionality; one does roughly the same thing when using an index to find the passages on a certain subject. The software, however, quickly provides a thorough and reliable index and then provides the user with interfaces for exploring those occurrences as a trace of a theme.

Synthesizing New Readings from a Text

In the case of Hume’s Dialogues, we first identified the words that we wanted to follow in order to study scepticism. To do this, we searched the Words in Entire Corpus list of Voyant for the forms of the word, using the pattern “s[ck]eptic” (which finds all the regular expressions of spellings with either a “c” or a “k”).11

Figure 3: Sceptic words in the Words in the Entire Corpus.

As was noted in chapter 1, using the Key Word in Context panel made it clear that in our edition “skeptic” is used to represent the school of philosophy, as in “the dispute between the Skeptics and Dogmatists is entirely verbal,” and that “sceptic” is used to represent individuals and their beliefs. Selecting all the sceptical words, we then got a distribution graph of where the thematic words appeared across the text. From the Word Trend graph it was clear that scepticism as a philosophical issue is dominant, at least lexically, at the beginning of the text up to chapter (or part) 3 and then tapers off, being dealt with less in any of the other parts. We therefore expected the issue to be explicitly raised in the first chapters and then returned to in the course of the dialogue in ways that might modulate our understanding.

Figure 4: Word Trend of sceptical words across parts of the Dialogues.

Figure 4: Word Trend of sceptical words across speakers of the Dialogues.

When we looked at the distribution of the words across the three speakers in the dialogue (ignoring Pamphilus, for the moment, because he is the narrator and not a speaker), we saw something interesting: Cleanthes, not Philo, uses these words the most relative to how much he talks. Even if Philo is the sceptic, it is Cleanthes who is fascinated by scepticism.

Cleanthes, despite talking about scepticism the most, talks about it only in the first half of the dialogue. After the initial chapters, he abandons the subject and lets Philo speak uncontested. His last sustained input on scepticism is in chapter 4. In short, Cleanthes raises the issue of scepticism in the first half; Philo plays with it in the second half; Cleanthes continually mentions scepticism in the early parts of the Dialogues as way of belittling what Philo has to say; Philo models it in how he argues. These visualizations suggested the need to investigate how scepticism is raised in the first chapters of the Dialogues, and how Cleanthes explicitly leaves the issue in chapter 4. Finally, we decided to see how Philo models scepticism in the rest of the Dialogues.

On Beginnings and Ends: Visualize the Flow of Words across a Text

Scepticism, in connection with natural religion, is one of the framing issues in Hume’s Dialogues. Using Voyant as a concording tool, we surveyed the way scepticism is introduced and read in extensive passages. We used the Key Words in Context panel to work through the concordance entries as “hits.” By default, Voyant’s preview includes five words on each side of the key word, but it can be expanded to see more context. We discovered that the dialogue begins with Demea congratulating Cleanthes on the education of Pamphilus. He quotes a maxim of the ancients: that students “ought first to learn Logics, then Ethics, next Physics, last of all, of the Nature of the Gods” (Hume 1991, p. 97). This unusual order of learning (unusual, at least, for a religious man such as Demea) leads Philo to congratulate him on his principles. The demotion of religious learning is a veiled promotion of scepticism, a move that raises Cleanthes’ suspicions. Pamphilus describes Cleanthes’ reaction this way:

But in Cleanthes’s features I could distinguish an air of finesse; as if he perceived some raillery or artificial malice in the reasonings of Philo.

You propose then, Philo, said Cleanthes, to erect religious faith on philosophical scepticism; … whether your scepticism be as absolute and sincere as you pretend, we shall learn bye and bye, when the company breaks up: We shall then see, whether you go out at the door or the window; and whether you really doubt, if your body has gravity, or can be injured by its fall (Hume 1991, p. 99).

Scepticism is linked with the titular issue of the dialogue, natural religion, and with the opening issue, education. Cleanthes also raises questions about the everyday practice of scepticism and common sense. He challenges Philo on the consistency of his scepticism and asks what he will do at the end of the dialogue. A few lines later, Cleanthes seems to anticipate Philo’s recantation, arguing that “it is impossible” for Philo “to persevere in this total scepticism, or make it appear in his conduct for a few hours” (Hume 1991, p. 99). Either Philo has to be consistently sceptical, questioning common sense exits like doors, or he has to be inconsistent and appear to only play scepticism as artifice during conversation. He is being put on notice that how he ends the dialogue matters. This foreshadowing sheds new light on Philo’s final position on scepticism.

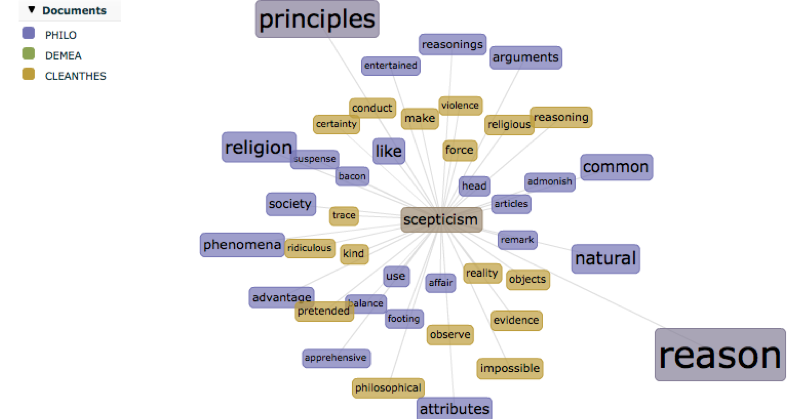

We then decided to explore the collocates using the Collocate Clusters tool. The words that collocate with (that is, occur within close proximity to) “scepticism” in Cleanthes’ and Philo’s dialogue illustrate some of the tension between Philo and Cleanthes.12 The Collocate Cluster shown in figure 5 also contains some unexpected terms Cleanthes uses in the context of “scepticism,” among them “violence,” “conduct,” “ridiculous,” and “pretended.” For Cleanthes scepticism is a “violence” that people impose on their “conduct.” It is “ridiculous” to reject Newton’s explications, and in fact sceptics end up following common sense despite their “pretended” scepticism. Exploring collocates reinforced and clarifies for us the disdain that Cleanthes has for Philo’s scepticism as a way of life. He focuses in specifically on sceptical conduct, not on the rationality of scepticism. He doesn’t attack the rationality of scepticism because he sees it as an excess or pretended rationality; he deals with it by repeatedly mocking it as a form of raillery or jest that is so impractical that it can have no effect.

Figure 5: Collocate Cluster for “scepticism”.

Cleanthes’ mockery of Philo’s scepticism peaks at the end of chapter 4 when Cleanthes contrasts the sceptic to the “ignorant savage”; scepticism is, for Cleanthes, a form of ignorance. He introduces ethical terms when he tells Philo “your sifting, inquisitive disposition, my ingenious friend … suppresses your natural good sense (Hume 1991, p. 120). Cleanthes patronizingly suggests that Philo’s scepticism is an error of excess “not from barrenness of thought and invention, but from too luxuriant a fertility” (Hume 1991, p. 120). It may not stem from ignorance, but nonetheless it leads into a form of ignorance by excess. Philo, Pamphilus tells us, “was a little embarrassed and confounded: But while he hesitated in delivering an answer, luckily for him, Demea broke in upon the discourse, and saved his countenance” (Hume 1991, p. 120). That Hume has Pamphilus interject here struck us as important, as it is one of the few times he interprets the dialogue for the reader. Whereas the interlocutor’s words dominate the Discourse, here Hume presumably wants to underline the ethical challenge to scepticism that temporarily silences Philo. How then does one answer such a personal attack from one’s host? How does one answer Cleanthes in front of his ward and student without being rude? Cleanthes doesn’t dispute sceptical reasoning (Philo could sceptically answer any rational questions about scepticism); rather, he characterizes scepticism as a futile excess of imaginative thinking. He is calling into question Philo’s good sense and behavior. A response or a rationalization, if even possible, would only reinforce Cleanthes’ point and demonstrate Philo’s further lack of good social sense. Here is the first hint of how Hume has Philo deal with Cleanthes. Hume deliberately changes the subject, though Philo will return to it later. Philo shows social intelligence by not taking the bait.

This brings us back to the practice of text analysis. There is real drama in this dialogue, and text analysis helped us find it. It would be easy to say that any close reader would have noticed this, and that may be true, but in our case it was through text analysis that we found the turning point where Hume uses Philo’s silence to make a point. Further, this dramatic dimension of scepticism as sensible practice, rather than philosophical practice, has not been dealt with adequately by philosophical interpreters, because it really isn’t about philosophical arguments or theories; it is about how you are a practicing and ethical intellectual in the world—something we all deal with, and something we are going to look at next.13 Following the logic of the arguments, as philosophers tend to do, one misses the social moves that become evident when the text can be concorded and reorganized according to different principles.

Skeptical Practice as a Response

Demea interrupts at the point of insult or ethical challenge and changes the subject. It is possible that even Demea feels that Cleanthes has gone too far and has exhibited unbecoming conversational behavior. The interruption leads to a series of chapters dealing with proofs of God’s existence—proofs that Philo demolishes in a virtuoso display of philosophical argumentation. Then, in chapter 11, Philo raises the problem that misery and evil presents for those who want to argue for God’s existence from the design of the world.

As has already been mentioned, this doesn’t mean that Hume drops the issue. Hume’s answer to Cleanthes’ challenge lies not in what Philo says, because one can’t really refute such a rude challenge, but in what he does in the evolution of the drama of the dialogue. Philo’s actions through the rest of the dialogue provide an indirect answer to the claim that he is excessive in his scepticism. Put simply, Philo is portrayed as a perfectly sociable character. When madness through excess of scepticism can be perfectly rational, no argument can decide the question. Instead it is the ongoing reasonableness of character that does so.

The reversal in chapter 12 provides an example of how a sceptic comes back to earth. Although Cleanthes has suggested that sceptics cannot gracefully return to the natural habits of using doors, chapter 12 shows us a sceptic who does just that: Philo returns to the natural pieties he was raised on. The reversal has, in this interpretation, a positive role in the definition of the character of the reasonable sceptic. It is not something to be explained away. It is the necessary return of sceptical flight, because true scepticism should be sceptical of scepticism itself. A sceptic who is truly consistent will be cognizant of the limitations of scepticism itself and will not take it too far, especially in the company of students. Good manners, reconciliation, and piety are what a self-respecting citizen returns to ultimately, especially when a guest.14

The reversal, though it may be philosophically contradictory, is dramatically realistic. How often do we back down on issues in conversation in order to preserve the peace with friends? How much more likely is it that Philo, having alienated Demea, would retreat at the close of a conversation to a position that is close to that of his friend, especially since this conversation takes place before the friend’s ward and in the friend’s house? In conversations it is common to challenge someone to get the conversation going and then to try to find a common ground at the end. This doesn’t negate the challenge; it mitigates it. The challenge still stands, because Pamphilus recorded the conversation. It stands to be reopened by readers who have to make up their own mind. Backing down in the way Philo does is far more likely to be the way a socially adept sceptic would finish a conversation with people he wished to keep as friends than the ways interpreters might wish for in the name of consistency. Nor does one have to interpret everything said in the reversal as ironic (an irony that Philo’s good friend Cleanthes would have noticed anyway, as Rich Foley points out).

Reversals are a dramatic feature of a number of other dialogues that can be traced back to Plato’s Phaedrus. In the Phaedrus, Socrates demonstrates to the character Phaedrus how he is a better rhetor than Lysias by first arguing one side of the question of who is the better friend and lover and then arguing the other. Socrates then makes up for this shameful showing off by engaging Phaedrus in dialogue—an even better way to write on another’s soul. The dialogue is uniquely suited to presenting different sides to a question, especially if the goal is to encourage readers to think for themselves instead of telling them which is the preferred position. Reversals are one way to ensure that the reader doesn’t leave the reading comfortably sure of what the author believes. They are a way to provoke the reader to decide what he or she thinks. The sceptic Philo shows that he can play both sides, and the author Hume makes it hard for the reader to take either side without thinking through the issue of scepticism as countless commentators have.

Scepticism at the End: Analytics Can Help to Find Patterns or Can Suggest What to Find

This brings us to the most important point to be made about how Hume portrays scepticism. As was noted above, the dialogue opens on the question of education and connects that with natural religion and scepticism. The dialogue also ends on the question of education and scepticism. We saw this when we used Voyant’s visualization of the results of correspondence analysis to show how words and chapters correspond. In the upper right quadrant of figure 6, one sees that the opening letter from Pamphilus, part 1, and the final part 12 cluster with words such as “scepticism,” “religion,” and “philosophy.”

Figure 6: Scatter plot of correspondence analysis of Dialogues.

Such text-mining visualizations are the opposite of the usual searching and concording techniques. They are exploratory. They illustrate the whole text in new ways that encourage you form hypotheses rather than answer them. Visualizations enable scholars to browse the big picture. In this case the visualization suggests that the dialogue is framed by chapters 0 and 1 at the beginning and by chapter 12 at the end, all of which have similar vocabulary. The visualization suggests that scepticism is raised at the beginning and then returned to at the end along with related philosophical issues. We can see the framing issues in the Words Trends graph reproduced here as figure 7 The hypothesis of framing was confirmed when we looked at Philo’s closing words, which take us back to the beginning of the Dialogues and to the issue of the education of Pamphilus:

Figure 7: Word Trends of “religion,” “philosophy,” “scepticism,” and “education.”

To be a philosophical Sceptic is, in a man of letters, the first and most essential step towards being a sound, believing Christian; a proposition which I would willingly recommend to the attention of PAMPHILUS: And I hope CLEANTHES will forgive me for interposing so far in the education and instruction of his pupil.28

We saw parallels between how Hume designs the dialogue to show scepticism at work and how Philo practices imaginative scepticism in his arguments. Hume presents us a Philo who has sparked and then managed the discussion that Pamphilus admits made a great impression on him.29 Philo’s imaginative scepticism is the dramatic engine of the dialogue. It provided Pamphilus with an actual example of the value of a sceptical education. By extension, it provided us with an example of scepticism in practice that is dramatically effective. Philo plays out what he advocates; he acts on his belief in the educational value of scepticism, and Hume shows the sceptic having an effect when he interposes in education. Philo (and on another level, Hume) handles the insulting challenge to scepticism not with arguments, but by showing us how educationally effective scepticism can operate in dialogue. Could you imagine a lively dialogue if Philo had not been inventive in his arguments? The dialogue itself is the answer to Cleanthes’ challenge.

Text Analysis Animates Questions

Cleanthes is also right: Philo is imaginative, and does indulge in raillery, at least toward Demea. The difference between the picture painted by Hume and Cleanthes concerns the worth of this imagination. For Cleanthes the arguments of Philo are an excess of imagination, no matter how rational. For the reader the scepticism of Philo is what animates the dialogue and provokes thought. Without Philo’s imaginative arguments there would be no dialogue worth reading in the first place. Pamphilus hints at this in his letter introducing the dialogue when he mentions how excited Hermippus, the person to whom he is sending the dialogue, was on hearing about the reasoning.30 For Pamphilus the conversation he had is worth writing down as a dialogue and sending to Hermippus precisely because of the “remarkable contrast in their characters” and the “whole chain and connexion of their arguments.”31 Pamphilus doesn’t tell us what to think; he shows us the dialogue.

The dialogue is an artifice that models how different educated people might talk about natural religion. Hume’s work is not merely philosophy; it is a work of ethics that uses the drama of dialogue to model behavior. It is an invention that Cleanthes might find excessive, but it is nonetheless educational in that it models pleasurable intellectual society. In his opening letter, in which he talks about what dialogues as a rhetorical form are good for, Pamphilus comments: “If the subject be curious and interesting, the book [dialogue] carries us, in a manner, into company, and unites the two greatest and purest pleasures of human life, study and society.”32

The ultimate irony is that the central arguments of the Dialogues are about arguments from design or artifice. On the one hand, Cleanthes sees pretense and raillery in Philo’s imaginative scepticism; on the other, he sees the design of God in the imaginative artifice of nature. Though he insults one form of creativity, he sees another as proof of the divine. Could Hume be presenting Philo’s scepticism—and, by extension his dialogue writing—as creativity analogous on a human social scale to the divine artifice we think we see in nature?

Skeptical Text Analysis

The computer-assisted practices described above have a number of virtues for those who want to use them to research their intuitions or the claims of others. They provide a different way of reading the text that is therefore not liable to the same types of errors as close reading tactics. That is not to say that there are not all sorts of ways text analysis can distort reading; it is just to say that the distortions are not those of the usual ways of imaginative reading and therefore serve as a useful alternative. What follows is an attempt to capture some of the virtues of skeptical text analysis.

Digital text analysis encourages a new form of dialogue. Digitally enabled hermeneutical practices involve formalizing claims, or parts of claims, so they can be shared and verified. What were we doing, then, when we tried text analysis? Like Philo’s scepticism, text analysis is not an answer or a theory. It struck us at a certain point that text analysis was a method (or performance) of questioning, a thinking through similar to Philo’s scepticism. We experienced new readings through re-examination. Rosanne Potter, in her survey of the statistical analysis of literature (1991), argues that “the vast mass of literary criticism rarely considers repeating or rechecking earlier ‘discoveries’ (usually simple assertions),” that replication is essential to the scientific process, and that scientific discipline will bring “a higher truth value to the practice of literary criticism.” We do not believe that text analysis can provide the certainty of scientific process, but we do believe that Potter is right about revisiting claims made about texts, and especially about re-viewing them through different instruments such as those visualizations provide. To support this value, we developed Voyant export features, some of which, like exported URLs, take the reader directly to certain states of the tool that support certain arguments.

Interpretive tools make it practicable to re-apply the essential tenet of the scientific method. Text-analysis readings, when documented, can be re-run by others. An interpretation that is presented through hermeneutica, so that it can be tried again, checked, and played with, is going to be more rhetorically convincing whether or not one believes in the certainty of science. It is convincing because readers can draw their own conclusions by playing with the evidence. It may be difficult to formalize interpretations so that they can be modeled with computers, but, insofar as one can try to formalize some claims for replay, doing so give readers a new view on your interpretation.

Digital analytics facilitate interpretive negotiation in new ways. Text analysis can enlarge a dialogue by providing formalizations for negotiation. If you check my interpretation and disagree with my claims, you can criticize the analysis, the choice of texts, the techniques applied, and the interpretations of results—something you can’t do if my interpretation is based on anecdotal quotes or on implied authority. The interpretive humanities are motivated not by a desire to prove things and move on but by a desire to renew understandings through conversations with the text and with others about the text. Text analysis as an interpretive practice is about an ongoing conversation about the text, but with the artifice of computing.

Computer-assisted text analysis is an imaginative practice that makes use of information technology. You could, like Cleanthes, accuse us of being too imaginative in our distortion of the text (and, for that matter, our distortion of interpretation). To many people, text analysis seems an unnatural practice that is not warranted by texts that are written to be read, not processed (though of course the processing can lead to new texts to be read). Likewise, visualizations can be imaginative but unintuitive and unfamiliar in comparison with reading texts. Critics of analytics call for a definitive proof of the value of hermeneutica in the form of an interesting and original contributions to scholarship made possible by computers. Needless to say, nothing satisfies such critics. Examples don’t satisfy, just as Philo can’t answer the challenge of excessive imagination, because a conclusion that can be reached only through computer-assisted interpretation will be too artificial to be interesting to a computer sceptic and because if such an interpretation it is believable anyway then the role of computing can be dismissed. That leaves only spectacle, but humanists are generally suspicious of the spectacle of visualization and poorly trained to deal with it.

Conclusion

In this chapter we have tried to show that interpretations do not stand alone such that they could be unambiguous champions for one method or another. Interpretations are influential to the extent that they are inscribed into dialogues valued in the humanities. We have to pay attention to how analytics and visualizations become part of the practices of interpretation and discourse about texts not only in the academic literature but also in data-driven journalism. That visualization and analysis are now part of computer-mediated discourse is no longer in doubt. Perhaps we should pay attention to them now.

In Reading Machines (2011b), Stephen Ramsay writes about how text analysis can deform a text, presenting different readings that provoke thought. We have made similar to points about text-analysis tools presenting new views that support reading (Rockwell 2003a; Sinclair 2003). Hermeneutica synthesize artificial views onto the text that encourage a reader to read it differently. The computer is a modeling tool for developing these different views, many of which are playful and a few of which are artful. The practice of text analysis is thus one of re-reading a text in different ways with the assistance of computers that make it practicable to ask formalized questions and to get back artificial views. This process can be a dialogue of sorts, enhanced by the hermeneutical tools we build. Like the artifice of Philo’s imaginative arguments, text analysis can enliven the dialogue one has with a text, which is at the heart of the humanities.

Perhaps we do text analysis just because these toys are available to us, much as Philo teased Cleanthes about God because he could do it. Ultimately, using computers to aid in analysis is in part an ethical decision in the sense that it is a decision on how to act as a scholar. On that, like Philo, we remain silent for the moment.

-

- 1. This tradition goes back to the Greeks—see Annas and Barnes 1985 or skepticism. In Hume’s dialogue they talk about Pyrrhonian scepticism which developed a practice of investigation designed to undermine any argument so as to lead to peace of mind. We will argue that Philo demonstrates an updated version of this in the dialogue.

-

- 2. This chapter is an artifice as it isn’t an actual transcript of what we did so much as a fiction describing how one can proceeded in theory if uninterrupted. In point of fact, this research was started in the 1990s by Geoffrey Rockwell and John Bradley when they were experimenting with visualization (1996). For more authentic examples of how people have used Voyant, see the Examples Gallery.

-

- 3. We used the Gutenberg edition in plain text UTF-8. We checked all quotes against the Tweyman print edition, and we have used page numbers from that edition. It should be noted that the Gutenberg version doesn’t identify the edition on which it is based, and that it differs in minor ways from the Tweyman edition (which is based on the handwritten manuscript in the National Library in Edinburgh).

-

- 4. Here we define a visualization as a visual representation of information generated by a computer (as opposed to an illustration drawn by hand.) There is a rich literature on visualizations (including pre-computer visualizations). Edward Tufte’s books (1983, 1990) contain many beautiful examples.

-

- 5. We borrow the term “pictorial concordance” from the first article written about textual visualization in Computers and the Humanities: “Prolegomena To Pictorial Concordances” (Parunak 1981.) In that article Parunak recognizes the pioneering work of John B. Smith, notably the 1978 article “Computer Criticism.”

-

- 6. Howard Rheingold documents this tradition of thinking of computing as a way to extend our capacities in Tools for Thought (1985). One of the most important proponents of augmenting our intellect was Douglas Engelbart, who not only wrote a report titled Augmenting Human Intellect (1962) but also developed an innovative system, called NLS, that demonstrated his ideas. An edited video of a 1968 demonstration of NLS is available.

-

- 7. Tweyman edition (Hume 1991), p. 172.

-

- 8. Pamphilus concludes this narrative framing of the dialogue as follows: “I confess, that, upon a serious review of the whole, I cannot but think, that PHILO’s principles are more probable than DEMEA’s; but that those of CLEANTHES approach still nearer to the truth.” (p. 185) This judgment is from the end of the text, the descriptions of Philo and Cleanthes at the beginning (p. 96).

-

- 9. Linguistic and stylistic analytics are typically not designed to assist in the interpretation of the text so much as for the purpose of using the text to interpret some other phenomenon, such as language use in a community or the style of an author.

-

- 10. See, for example, Mossner 1977 or Foley 2006

-

- 11. This search uses regular expressions to find both “sceptic” and “skeptic” and to find different endings. For more on regular expressions, see http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/services/helpsheets/unix/regex.html.

-

- 12. We produced this graph by using the Collocate Clusters tool in a different “skin” of Voyant. This skin is a different arrangement of Voyant tools that is optimized for exploring words that collocate with (i.e., appear near) a key word.

-

- 13. Foley (2006) is an exception. He explains Philo’s reversal in chapter 13 as Hume showing us how a character like Philo, no matter how sceptical, will revert to some level of belief in divine design if indoctrinated from an early age. In effect, Philo exemplifies how someone educated in the fashion described at the beginning of the Dialogues will be comfortable arguing skeptically, but will revert to the piety he was taught when young and impressionable.

- 14. If we were to take this line of inquiry further, we would look to Hume’s writings on and his history of intellectual manners. What did Hume have to say about intellectual society and wit? How is he supposed to have behaved in society? Did that matter to him?